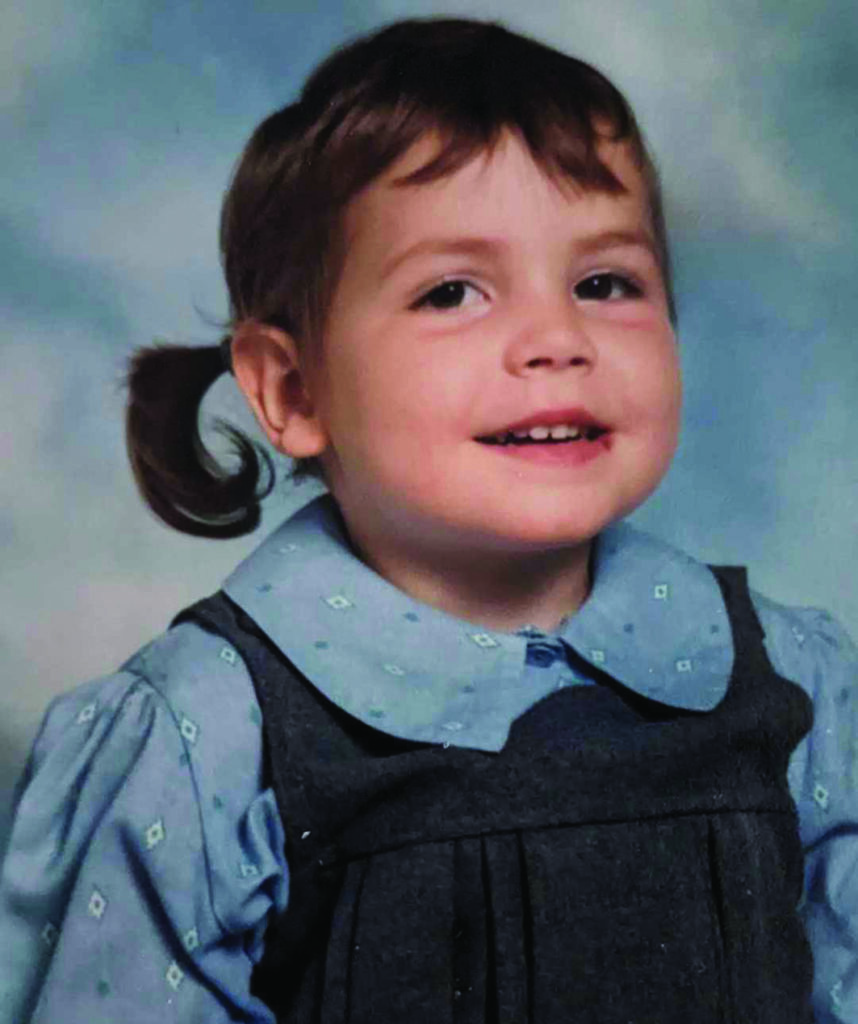

Gemma Lees looks at the differences between her experiences in school as an undiagnosed neurodiverse child in the 80s and 90s and her son’s experiences of a relatively early autism diagnosis at the age of 7.

‘Why is everyone suddenly getting diagnosed autistic?’ is a genuine question that I’ve been asked, and any quick internet search will reveal that there are many others asking such questions and making ill-informed comments regarding ‘lack of discipline nowadays’ and other such well-worn talking points.

Neurodivergence or neurodiversity, which incorporates dyslexia, dyspraxia, dyscalculia, ADHD, autism, Tourette’s syndrome and more, is estimated to affect 1 in 7 people in the UK. Neurodiverse brains work differently from the average or ‘neurotypical’ brain and this can lead to problems with socialisation, learning in a traditional school environment, sensory input from the world around us, motor functions, impulsivity and anxiety.

I have always struggled with all of the above. I started primary school in 1987, eleven years before sociologist Judy Singer coined the term ‘neurodiversity’. We certainly still existed in the Eighties, but a lot of us flew under the radar, especially girls, as although there are genetic factors that mean that boys are more likely to be autistic, girls go disproportionately undiagnosed. We tend to find ‘masking’, or imitating socially appropriate behaviours easier to do. Girls are also traditionally socialised to be nice, passive, accommodating and nurturing, and although this wasn’t something that was reinforced at home, school teachers would definitely tell us to ‘play nice’ and ‘act like a proper young lady’ often.

And that was my main issue, it was ‘acting’. I felt like everyone else in the world had been given the rule book on how to interact with others, how to make and keep friends, how to sit still and concentrate in class, and my copy had got lost in the post. Even as I started high school, in 1996, with the internet in its infancy, there were no outlets for me to try and find out why, although I knew that I was clever, school was such a hard slog and why the social aspect of it, in particular, was such a challenge for me. The constant masking was exhausting, and I became an intensely anxious teenager.

It’s now generally accepted that autism and neurodiversity have existed in humans for millennia. ‘Early infantile autism’ was first described in 1943 by psychiatrist and physician Leo Kanner, then thought to have been a form of childhood schizophrenia caused by cold and indifferent ‘refrigerator mothers’, as described by psychologist Bruno Betteheim. Research carried out throughout the 1980s and 1990s led to loosened diagnostic criteria for ASD and the ICD-11 which will be in full use by the NHS by 2026, highlights the fact that older individuals and women sometimes mask.

So, fewer people were diagnosed with autism in the past because it was just less understood. The mothers of those with a diagnosis could be blamed and stigmatised as unloving, and autistics were institutionalised and given experimental behavioural treatments or misdiagnosed and given inappropriate psychiatric medications.

I’m now the proud mum to Tommy, who was diagnosed with ASD at the age of 7. Although there is certainly a lot more understanding of autism now, my husband and I were still very lucky that his nursery teacher was an ex-SENCO, and she picked up on the signs and referred him for diagnosis. The support we received as parents and the one-to-two teaching with a specialist teacher that his primary school put into place was excellent, and Tommy is today an intelligent, quick-witted, charming and caring 11-year-old. He is talented in the areas of computing and coding and recently taught me how to make a PowerPoint presentation. He is also proud of his neurodiversity.

We chose a specialist school for Tommy’s secondary education and we, and more importantly he, is loving it. The curriculum is centred around each child’s strengths and learning styles, the teachers genuinely care about their pupils, and it has both sensory and soft play rooms.

The internet means that I can connect to other parents, easily do research and find video and other content to educate myself on Tommy’s needs. I can also connect with other parents and find social activities for Tommy, including swimming with a sports club for disabled children and a drama club for disabled children, both of which he loves and allows him to socialise in a space in which he feels safe and supported in.

As for me, I was finally diagnosed with dyslexia and dyspraxia when I was 21 by my under-grad university and I’m currently being assessed for autism, after my psychiatrist found out Tommy’s diagnosis. At 40, I’m finally getting the validation that there was nothing wrong with me at all, just in the general understanding of autism of the time. What a difference a generation makes!

Gemma Lees

Gemma Lees is a Romany Gypsy and a disabled and neurodiverse journalist.

Instagram: @gemisace