Frances Clark’s strategy to help deaf children develop a conversational rally.

Louis’s parents found out he was deaf when he was 18-months old. Keen for Louis to learn to listen and talk, his family joined a specialist Auditory Verbal therapy programme to support his spoken language development and he started school with speech and language ahead of a typical child his age.

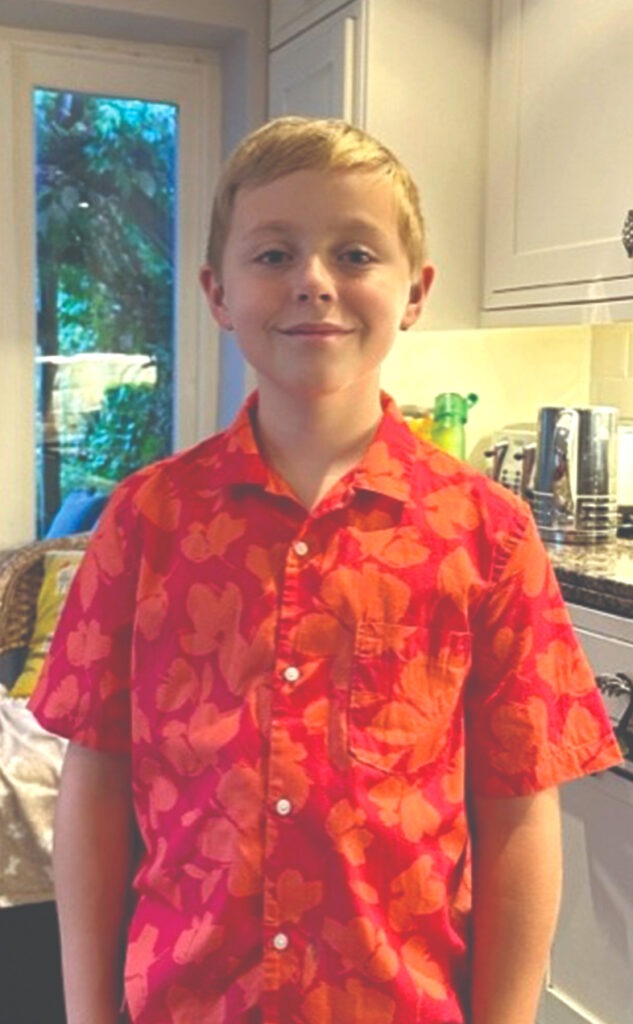

Now at secondary school, Louis loves doing typical 11-year-old things: playing computer games, reading Anime books and playing tennis. But Louis’ ability to serve and return began long before he learned how to play tennis. Serve and return is an important strategy in speech and language development. Just as Louis has been coached on developing his skills on the court, his parents were coached to recognise his communication initiations (serves) as a young child and return them in a way that facilitated conversational rallies.

Studies show the impact of conversational turn-taking between infants and caregivers and how conversational tennis impacts neural language processing, vocabulary development and childhood mental health.

How can professionals working with deaf children support “serve and return”? We know some parents find communicating with their deaf child difficult. They may be unsure when their child has “served” communication as they may be doing something different to what parents may typically expect. For example, they may not vocalise at the same time as their typically hearing peers or they may gesture or use their eyes.

The Harvard University Centre on the Developing Child has identified five steps for using the Serve and Return strategy. These are a useful tool in coaching parents and caregivers so “Serve and Return” becomes part of daily life.

Step 1: Recognising a communication serve

Therapists coach parents on recognising non-verbal attempts at turn-taking and how to share their child’s focus of attention. Considering questions like, “what do you think he is trying to tell you?” or “what is she thinking?”, while spending time observing how a child initiates communication. For example, do they move their arms and legs? Do they vocalise? Do they look at objects that interest them and back at the parent? Encouraging parents to WAIT for their child’s serve can be really powerful.

Step 2: Returning the serve

Returning the serve encourages children to take another turn and builds neural pathways for conversation. So, if a child claps and their parent laughs, the child is likely to clap again to receive the same response. This might continue for a few turns of clap-laugh-clap-laugh and a conversational rally is developed.

Step 3: Using words

To develop listening and spoken language, professionals encourage parents to return the child’s communication initiation by using words and phrases like, “you’re clapping!” or “you want the ball!”, and then giving the child the ball and waiting for them to continue the conversational rally by taking the next turn. It doesn’t matter what is named in this situation it could be objects, actions, feelings or expressions, like “oh, that’s so funny!“. The same principle can be applied for children learning signs.

Step 4: Waiting

Waiting is crucial to enable the child to respond to the parent’s turn in the interaction. Often, waiting can be the hardest strategy to use as parents are biologically programmed to fulfil their children’s needs. For example, if they know their child is hungry, it might be difficult to wait for their child to vocalise or sign “more” or point to a banana. Waiting is crucial for the child to organise their thoughts. Particularly for vocalising, this can be difficult for a child who doesn’t have consistency in hearing their own voice. When a parent waits for a sound or word then responds to that sound or word, a child learns that their voice is powerful.

Step 5: Practising conversational endings and beginnings

By observing a child’s behaviour, parents can identify when they are finished with a particular interaction, activity or thought. They may move away from something, push an object away, avert their eyes, wave or vocalise. To develop listening and spoken language, parents are coached to provide words for what their child is thinking like “all done!”, “finished!” or”Bye bye!”.

The concept of “Serve and Return” has formed the backbone of many intervention sessions for children like Louis. His Mum Yvonne explained “Auditory Verbal therapy equipped us with the right tools and techniques to help Louis develop his auditory memory and speech. We feel it really fast-tracked his speaking and his sentence construction and gave him a range of skills. He has developed amazing levels of concentration and uses a rich vocabulary which continues to amaze us.”

Louis’s family attended an Auditory Verbal therapy programme delivered by specialist speech and language therapists who have undergone around three years additional post-graduate training to become certified Listening and Spoken Language Specialist Auditory Verbal Therapists.

We know that training to become a tennis player is not a matter of picking up a racket and heading for the nearest court, it takes preparation, mindset, skill and practice. Developing communication for children who are deaf is the same, parents arrive at the court without a racket and need a coach to support them.

Stories like Louis’s show that with early and effective support deaf children can achieve their potential both academically and through sport and hobbies. Every deaf child should have access to early and effective support to develop language and communication, whether they use sign language, spoken language or both.

Frances Clark

Frances Clark is a Senior Auditory Verbal Therapist and is the Clinical Lead for Auditory Verbal UK. For information on AVUK’s programme of Auditory Verbal therapy.

Website: avuk.org