When teaching Maths to children with special needs, it is essential for us to understand how mathematics begins and develops. Les Staves explains.

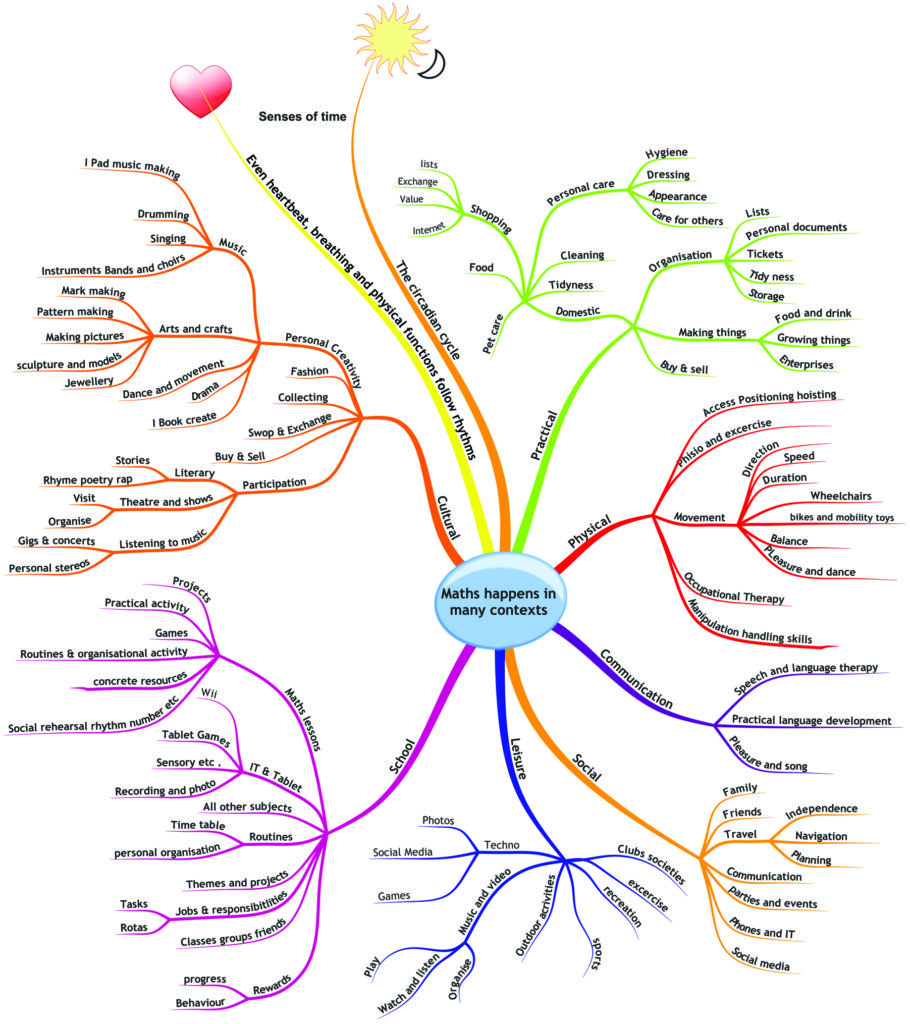

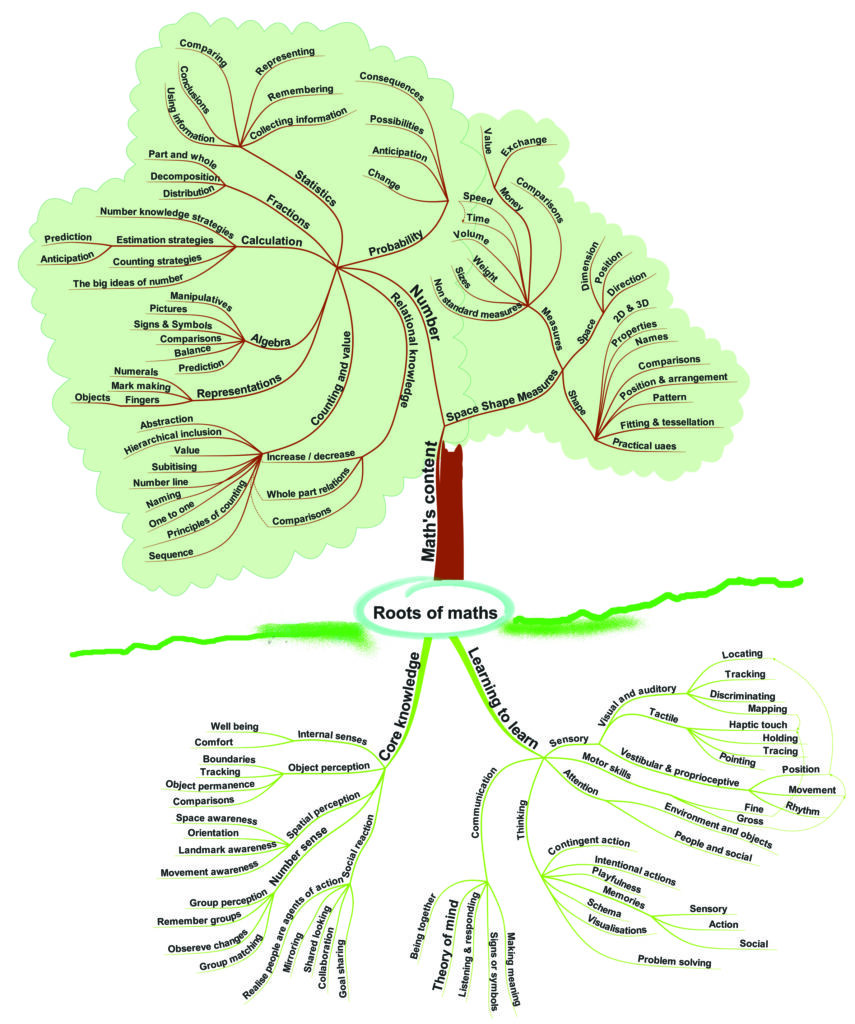

Maths is not just an abstract subject—it is a living necessity. We use maths wherever we encounter changing quantities, or for any practical use of shape, space, direction, time, sequences or patterns. Mathematical learning begins by developing a root system of learning. It lies deeper than the starting point described by conventional curriculum ideas, that maths begins with numbers. There is a great deal of maths to be learned before numbers can be formalised. Although mathematics is usually considered an abstract subject, it has its roots in sensory development and practical activity. These roots are in the skills and knowledge that the mainstream curriculum takes for granted, because it assumes they have already been learned before school. Children must first master the root skills, and any curriculum for children with special needs must provide experiences that nurture these roots. This requires a curriculum that embraces the whole child’s development. It must also recognise the vital aspects of sensory and physical learning, and delivering mathematics with an emphasis on practical working and social interaction.

Root systems are complex and capable of branching to finer elements. For example, if we were to expand upon the root branch labelled Schema, which is an extension of the Thinking branch on the Learning to learn side of the root system, we would open up a massive area of thinking about the roles of repeated actions in children’s early learning processes. Cathy Nutbrown wrote a whole book about it. Threads of Thinking is still a classic text.

Core Knowledge

The root branches stemming from Core Knowledge (see the root diagram) outline knowledge that children usually have at birth, or develop rapidly from the first days or months. They include social reactions, which are immensely important to developing communication and learning capabilities. Researchers have shown that newborns have perceptual tendencies and reactions that they build on as young infants. With these, they begin to make sense of their surroundings and their interactions with things and people. Because these stem from typical biological activity, we might not think of them as skills to teach in school. But if there have been early difficulties, we should consider what effects the difficulties may have had on the development of core knowledge, and attempt to mitigate them.

One aspect of core knowledge is Spatial Perception. Infants are attracted to the contrast of light and shadow, and they follow movement. From this, they build awareness of space and shapes. This is how they build the mental maps that are an innate part of functional geometry. Another related aspect is Object Perception, which is the ability to perceive and distinguish objects from background. Together, both these perceptual skills have obvious implications for understanding the dimensions of their world and the things in it.

Number Sense

Number sense is the ability of infants, even in the first few weeks of life, to identify when there are quantitative differences between small groups. This is the perceptual seed from which appreciating number and understanding number names first grows. Another aspect, approximate number sense, is about developing the ability to discern which of two groups is larger. Appreciating such comparisons, to make choices, is one of the first forms of mathematical reasoning. Research suggests that early difficulties with these aspects of core knowledge may lie behind Dyscalculia and other mathematical difficulties. The development of number sense is going to become an important part of both the special and mainstream maths curriculums. The process called subitising, which is the rapid recognition and naming of groups (a skill which springs from number sense), is now being mentioned in curriculum documents and teaching recommendations, for example, in revisions of programs of study and in the Maths Hubs training Mastering Number at Reception and KS1. It is also featured in online resources websites such as Twinkle.

Learning to learn

Children usually build upon the core knowledge they are born with by reacting in their environment using physical, sensory and mental skills that help them gather and remember information. We might think of these skills as their tools for learning. Children use them to change things to achieve what they want. The tools used for learning include the Senses, Perception, Attention, Memory, Manipulation skills and Movement skills, and alongside all these, children also develop Communication skills. Each of these leads us to a multiplicity of necessary subskills, which could be represented as further extensions of the roots diagram.

The cycle of learning processes

In the natural course of their learning, children use their senses, and all their other learning tools, whenengaging in the process of play. The cycle of play starts with curiosity, and moves through exploration, problem solving, to achievement of goals and evaluation, before starting its next cycle. This is the human cycle of learning. In fact it is the same process as scientific investigation, or many other development activities. Unfortunately, play has been undervalued, or even belittled, in curriculum models beyond early years. However, it is now worthwhile noting that the Engagement Model introduced in 2022, to support SEND assessment for children working below NC levels, actually evolved from the cycle of play. Does this mean that assessment could move towards reflecting the quality and value of refining children’s learning processes, as well as reflecting on the subject content that children gain?

Discovery and skill refinement

When children are engaged in exploring using various skills, the accrued practice hones their skills, and they become progressively more fluent, more efficient users of their own learning tools. During explorations children are in effect learning to learn more effectively.

Special needs and tiny skills

With most children, subject curriculum takes sensory development, perceptual and attention skills for granted. Consequently, beyond early years settings, teaching these skills is not acknowledged as part of the traditional curriculum. However, some children’s learning difficulties stem from inadequacies with these learning tools. So helping children to develop skills needed to learn to learn should be a priority in the special curriculum. They are not only important for children’s general development, but because they enable the exploration of objects, quantities, shape, space and time. They are skills that make the learning of practical maths possible. Recognise the value of the small skills that contribute to wider learning.

Living Maths

Maths is an all-encompassing requirement of life. It’s a cultural tool. It’s everywhere around us. The real world is teeming with opportunities to teach its language. Whatever circumstances you teach through, be it sensory experience, life skills, games, social and cultural events, or even when your curriculum has become more formal, it is your job to bring out its life and make it live vividly.

Les Staves

Les Staves is the author of Very Special Maths, which has had worldwide influence. He has worked with children with very special needs since 1973.